It’s undeniable the role the railroad industry played in Altoona. After all, our city was literally founded by the Pennsylvania Railroad Company. Because of this, it is hard to go a few blocks without being reminded of this history. We are even lucky enough to have a whole museum dedicated to Altoona’s rail history right in our backyard. Unfortunately, for far too long in many conversations about Altoona’s, and Blair County’s history overall, we seem to ignore the contributions black people have made even in the face of so much adversity. However, in recent years there has been a push to inform the community about these feats.

In 2020 a mural was unveiled on a wall at the Altoona Pipe and Steel building. This mural was created during the “Windows on Altoona” summer art camp taught by Deb Bennet. The mural features William Nesbit, a lesser known black civil rights activist who worked to progress the rights of black people. His efforts not only contributed to Altoona but worldwide.

When he visited Liberia with the Hollidaysburg family (Deputie or Depuitee) and Samuel Williams of Johnstown in 1853, Nesbitt became even more outspoken in his opposition to the colonization of Liberia. He chronicled his time in the West African country in his 1855 pamphlet titled “Four Months in Liberia: African Colonization Exposed.” In this provocative and insightful pamphlet, he made people in the states aware of the violent colonization spurred by the American Colonization Society. He traveled throughout New York and Pennsylvania speaking out about the issues of colonizing Liberia. While on these travels around Pa. and to Ny., he met with influential civil rights leaders like Morris Chester, Octavius Catto and Fredrick Douglas.

Liberia is a West African country, founded by freed US blacks and freed former US slaves,

— African american history teacher Carolyn Kline said.

Nesbit was also very active in the Altoona community; he served as a Notary Public and was Blair County’s candidate to the Pennsylvania state convention. Most notably, Nesbit served as the first president of the Pennsylvania State Equal Rights League. With this influential role, he was able to successfully lobby the United States Congress to pass the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. When he died in 1895, his obituary wrote that “His entire life was given to the elevation of his race.” Today Nesbit’s legacy lives on in our community with Blair County’s chapter of the NAACP being led by Altoona alum Andraé Hoalsey.

“There were a number of black leading black men of that time. So you’re including Frederick Douglass, for example, in that group. There were subordinates in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, along with William Octavius Cato out of Philadelphia. Dr. Martin Delaney, Pittsburgh, for example. All of these men had one thing in common and that was to actually to get citizenship for black men,” Harriet Gaston, a local historian and an undergraduate studies adviser at Penn State Altoona said.

Black history has also been overlooked in neighboring Blair County cities like Hollidaysburg. In 1856, Daniel Hale Williams III was born to Daniel Hale Williams Jr. and Sarah Price Williams from Baltimore. Growing up on 315 Blair Street, he had seven siblings and helped his father at a barber shop before he decided to go to Chicago Medical College. After graduating in 1883 there were only three other black medical doctors in all of Chicago. Dr. Williams decided to serve disenfranchised peoples as a physician at the South Side Dispensary and as a surgeon at the Protestant orphan Asylum, later he was the surgeon in chief of Freedmen’s Hospital in D.C. However, the lack of opportunities for black medical professionals were scarce, so he founded the United State’s first interracial hospital in 1891- Provident. Aside from providing medical care to black patients that would otherwise be turned away or given below sub-par care, Provident Hospital also offered training to black interns and created the first school for black nurses in the country. Additionally, while at Freedmen’s in D.C., Dr. Williams founded yet another school for black nurses.

When the United States Colored Troop (USCT) was established in 1863 and black men volunteered or were drafted for the Civil War, his oldest son, William W., joined the 54th Massachusetts Infantry (of the movie, “Glory” fame,) along with several other black Blair County residents and he was wounded at the Battle of Olustee, Fl. in February of 1864,

— Kline said.

These accomplishments would be plenty for anyone, but not Dr. Williams. While at Provident on July 10, 1893, Dr. Williams performed the first open heart surgery in the United States. This daring and trailblazing operation was done at a time without blood transfusions, x-rays, or really any tools associated with modern medicine. Despite this, the patient, 24-year-old James Cornish, who suffered a severe wound of the pericardium, lived at least an additional 20 years.

Far too many do not know about this truly remarkable man, which is why in recent years there have been efforts to make his history known. Local artist Barbara Karcher painted Dr. Williams in a lab coat at the Hollidaysburg Library.

Along with the library painting, an acrylic portrait of Dr. Williams painted by Altoona artist Joe Servello hangs in the lobby of the municipal building on Blair Street near where he was born. And although 315 Blair Street- the house he grew up in has since been torn down, a historical marker stands where his childhood home once was.

While these recognitions are a step in the right direction, they don’t have the same force behind a class for example that would teach students or the community at large of Dr. Williams and other overlooked black people’s accomplishments in the face of struggle. Additionally, a major aspect of black history is about how the past greatly impacts the present, unfortunately, something none of these acknowledgments really do. For example, none give mention to the fact that black people face negative health disparities due to systemic racism that percolates in the medical field.

In some classes around AAHS though, teachers are trying to bring to light the struggles faced by black people in the United States. Last marking period, English teacher Anthony DeRubis had his AP Language students read “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.”

“Our country is made up of a plethora of different cultures and different groups of people. So I think it’s important in the classroom to read a diversity of literature to understand the American experience overall,” DeRubeis said. “There were voices that were suppressed in higher education because of a non-white connection, and I think it’s important to highlight those voices today in order to meet a diverse audience not not everyone’s the same.”

This harrowing true story follows Henrietta Lacks, a young black woman with cervical cancer from Maryland. While undergoing what she believed to be treatment for her cancer at Johns Hopkins in 1951, her doctors stole her cells. Today the immortalized cell line that stemmed from her HeLa cells makes pharmaceutical companies billions while her family was only recently able to reach the first settlement with a biotech company that used her cancer cells nonconsensually.

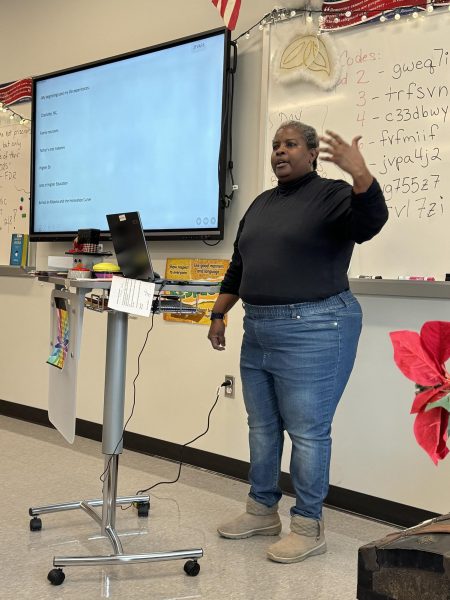

Another class at AAHS is solely focused on teaching about black history is Carolyn Kline’s African American History Class. In 2022, then junior Anaiyah Crone started Altoona’s first class that focused on African American history after realizing no classes at AAHS teach about black history despite it being everywhere. The semester-long course has six units ranging from early African kingdoms to modern day.

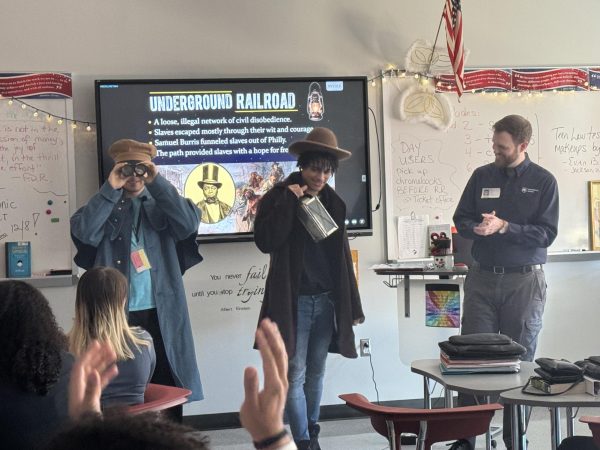

“This year I invited Ms. Harriet Gaston from PSU Altoona who is a very involved local historian, especially with the history of blacks in Blair County. I also invited Dr. Jared Frederick of PSU Altoona, who talked about the Underground Railroad and Altoona’s place in it,” Kline said.

It is important to recognize the triumphs of black history in Blair County, but it is equally crucial to point out the darkness as well. While many associate hateful groups like the Klu Klux Klan with the South, the KKK had extreme popularity in Pennsylvania. In the mid-1920s, the Klan had 250,000 members in Pa. The Klan was appealing to white Protestants and not just men as typically assumed. During this time, there was a movement in this heinous terrorist group to be called Klanspersons. According to writer Philip Jenkins, this “highlights the movement’s broad appeal to Protestant women, and its use of ideologies of sexual purity and white womanhood.” This support coming from a wide array of people was regrettably most pronounced in our area. Of the 250,000 Klan members in Pa., about a fourth were located in the areas surrounding Pittsburgh, which includes Blair County. In the entire nation, the city with the highest proportion of Klan members was none other than Altoona.

“Below the Mason Dixon line groups like the Klu Klux Klan were targeted towards black people. Above the Mason Dixon, you’ve got something else going on and that’s immigration from Eastern Europe. Similar to what I’ve heard in today’s society, people said they’re taking their jobs,” Gaston said. “There were instances that occurred in Altoona where black folks gathered in the Klan. Most of the presence of the Klu Klux Klan occurred after World War One.”

As a representative of the African American History Foundation, Gaston has also helped to bring celebrations of black culture to the area, most notably with her involvement with the Blair County African American Heritage Foundation.

The African American Heritage Festival actually started in 1994. It took place every year in the summer until 2014. And then at that point, unfortunately, there were funding issues. But the purpose of the festival actually was to help promote the documentation and the sharing of black history,” Gaston said.

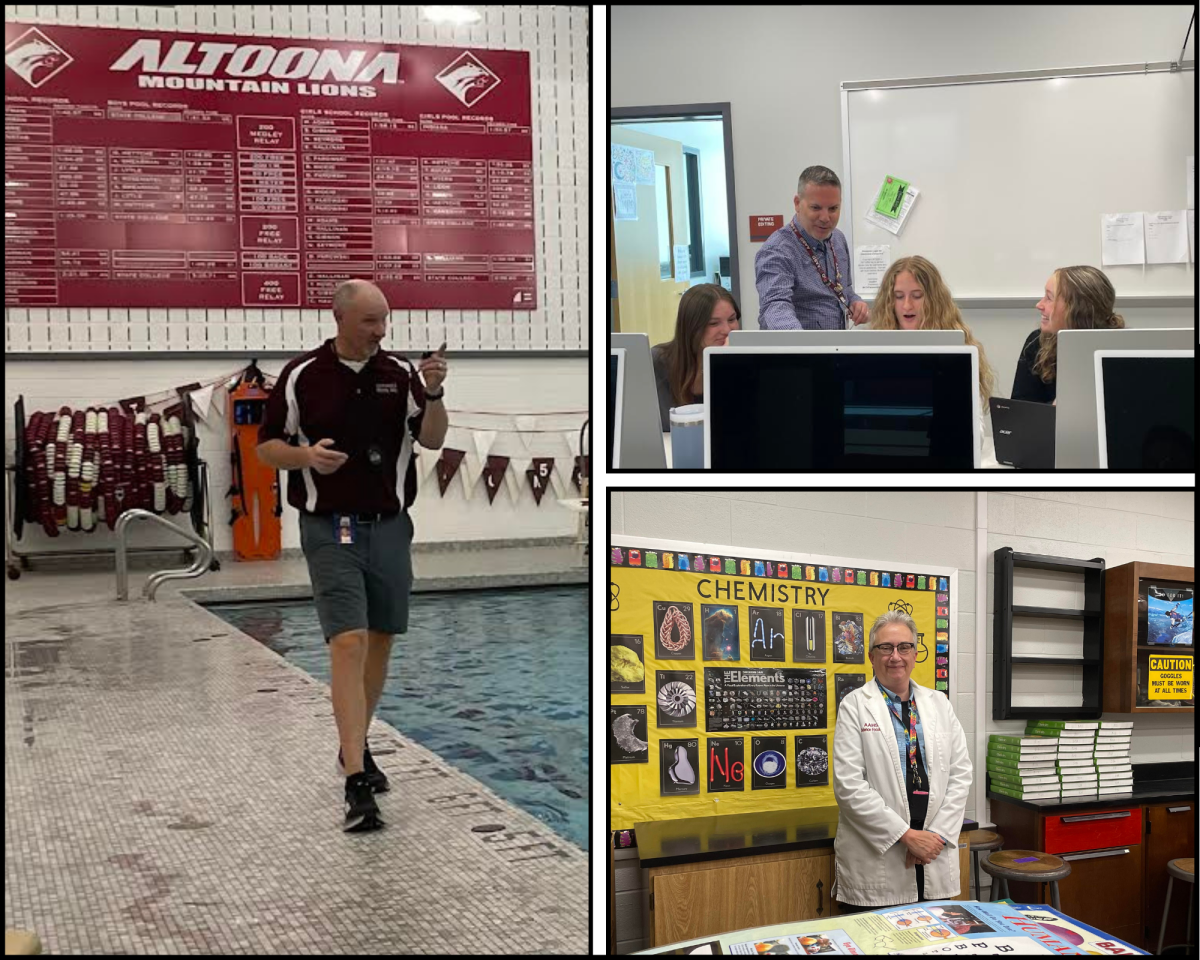

![Chemistry Champion. Chemistry teacher Christine Falger was designated a comic book superhero during the 2023-2024 school year. She poses with her seventh period honors chemistry class, accepting the award. This is a result of the Climate and Culture squads work around the school, which focuses on building teacher morale. [Being part of a squad] is a big time commitment. We as a squad are required to give one hour of time a month, I am probably anywhere from eight to 12 hours a month, Krug said. [But the squads work] can make the high school a better place. I am really lucky to work with a number of teachers who also feel the same way. Even if we are doing more than some squads at the high school, we still feel like what were doing is really important. (Courtesy of James Krug)](https://aahsmountainecho.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Chrissy-Falger-Comic-Book-Superhero-Honors-Chemistry-1-e1712174011111-1200x738.jpg)