Interpreter visits Sign Language Club

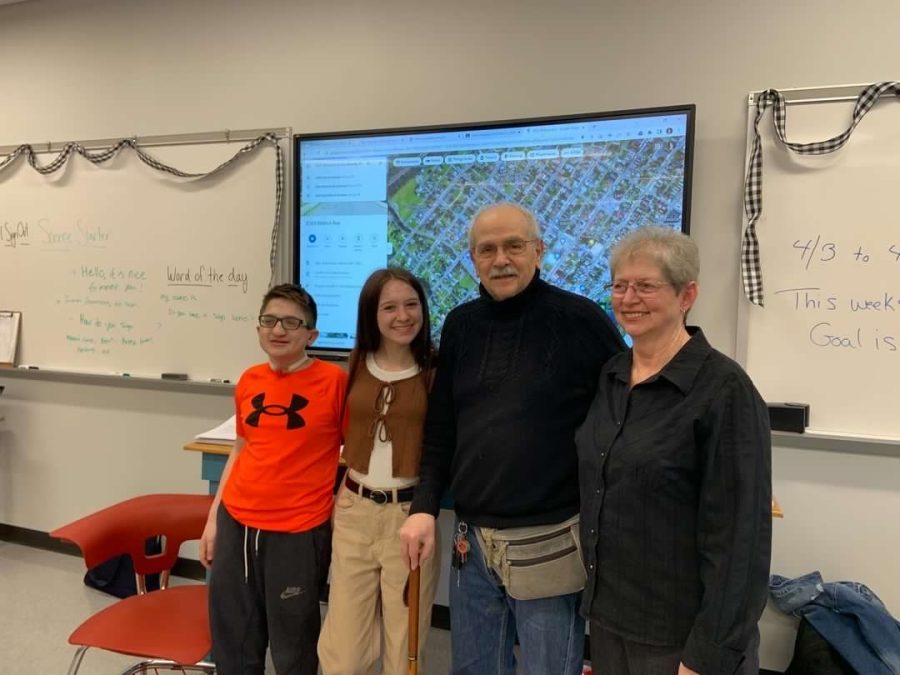

Betty-Jane Neely, Alfred Corrado, Aydan Roland and Sean Roland pose for a photo.

The Sign Language Club (SLC) had an opportunity to have an interpreter and a former Altoona resident come to the school and provide knowledge about deaf and hard of hearing culture. Other schools in the district have an interpreter who works at the school.

“They are highly intelligent in what they do, so watching them come to the school and present what they have learned/how they communicate is so interesting to watch and observe. I loved watching how they communicated with one another, as well as to the club members. When signing, they do not use every word in the sentence as we would in English. For example, when Alfred was saying where he went to school, he said ‘I school Gallaudet Washington DC,’ instead of ‘I went to school at Gallaudet University in Washington DC.’ This is a school that works with people who are deaf and hard of hearing, being able to help those [deaf and hard of hearing people] get an education,” SLC president Adyan Roland said.

American Sign Language is different from the English language. According to interpreter Betty-Jane Neely, ASL does not use be verbs, which alters the language.

“I believe that everyone should learn the basics when they are little so that as they grow older, they are able to communicate with people around them who are deaf or hard of hearing. Plus, it makes you stand out knowing a skill or language that most people do not. You are able to teach other people around you signs, in turn growing the community,” Roland said.

Speech teacher Shelby Lenhart hopes the high school students will have access to an interpreter one day just like the junior high school as well as one of the elementary schools.

“We may eventually have an interpreter who comes to the high school. So it is really important for students to know if you have a friend in your class who has an interpreter you want to talk to that student by looking at that person, making eye contact with that person and letting the interpreter interpret,” Lenhart said.

According to Roland, the SLC had a good time, and it was a beneficial learning experience for those who are involved.

“It is so cool to watch someone sign and learn what they are saying in a different way. It shows our society that being deaf and able to communicate in sign language is a rare skill to people our age,” Roland said.

Roland’s experience with interpreter’s did not just begin inside the school.

“Sean, my brother, has had an interpreter his whole elementary school career. As he got older, he grew to use his words in speaking rather than signing, so he does not need one anymore because he has grown tremendously in his speaking skills,” Roland said.

Neely, as well as Roland, have connections to those who are hard of hearing and or deaf.

“My introduction to American Sign Language (ASL) began when in junior high. A friend taught me the alphabet. We had fun talking to each other by fingerspelling. If you take the time to learn the alphabet, the Deaf [community] will appreciate that you cared enough to learn that. Most conversation is not finger spelled, but uses other hand signs or gestures that portray words or ideas without spelling out each letter of each word,” Neely said.

Neely learned the basics of ASL not knowing it would become a big part of her life.

“Years later, I had a neighbor who had a deaf son. She and I attended some classes to learn ASL together. The classes were taught by two deaf adults. One used Signed English and the other used ASL. Signed English signs, or spells, every word in English word order. ASL is more concept by concept – with its own syntax (word order) – not always the same as English. It is a whole body language using not only hand and finger shapes but also facial expressions (mouth, tongue, eyebrows).” Neely said.”

As ASL is becoming more recognized inside schools, more opportunities are being open for those who are deaf and or hard of hearing as well as those who are not.

“It’s hard when you talk to someone who has an interpreter. I know I want to look at the interpreter, but it is important to make eye contact with that person and not the interpreter. Then when you’re talking and you respond, you want to look at the person you are responding to and not the interpreter,” Lenhart said.

Hi! My name is Kirstyn Hood. This is my second year in the journalism program, and my first year of the AAHS Mountain Echo staff. I have enjoyed writing...

![Dedicated. Teachers who live far away commute for at least an hour to work each day. [Made with Canva]](https://aahsmountainecho.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/teacher-commute-picture-424x600.png)